It’s a hot topic in the sports science world as everybody is constantly talking about High Speed Running or High Intensity Distance. It makes sense as higher velocity running has a significantly higher cost on the body as a whole and therefore should be closely monitored and tracked (if possible). But when it comes to the upper threshold of those speeds, how often should we dose it in and what are some components that should guide us on how much to give? Below are three thoughts I had on the matter:

85% is different than 90% and 90% is different than 95%

While we want to think of HSR as being anything over a certain percentage, we need to keep in mind the different effects these percentile jumps will have on our athletes physiologically. YLM Sports Science recently did a review of a study by Heiderscheit-Chumanove J Bomech (2007) showing that running at 100% of one’s maximum speed produced an eccentric load that is 50% higher than running at 80% of one’s max speed. Faster speeds provide exponentially higher loads and undoubtedly will take a greater toll on athletes physically. We shouldn’t see a 5% increase in speed as a 5% increase in load to the body. It just doesn’t add up that way although it would be nice if it did.

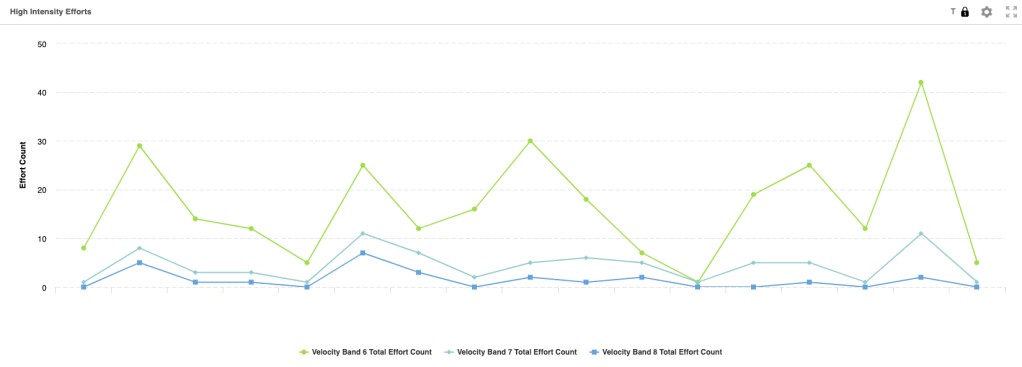

Don’t fall into the trap of lumping all high-speed running events into the same category. Know the difference between your bands and how often your athletes hit them. For me, athletes will often hit 60-75% of their max speed >40x in one match. Depending on their position, they will then hit 85-100% for roughly 1-5x in a match. Even if you don’t see a spike in total sprint efforts, it’s possible that they also went from hitting 4 efforts at 85-87% in 1 week to 3 efforts at >95% the next week. On paper it may seem the same but in reality, it’s very different. Below is a widget I’ve created that shows ways to longitudinally track the # of efforts at various speed thresholds. Depending on match or week averages, it allows me the ability to dose appropriately or attempt to limit an athlete when they’ve far exceeded or achieved less than their historical averages.

Control the controllables, dose it in

I am sometimes dumbfounded as I look at my own historical data in that sometimes athletes will go for an entire month without hitting “sprint-speed” in a match. This is very position-specific but depending on a lot of factors, it can definitely happen. If you don’t dose in max effort sprints in training, they could go a very long time without hitting near their max speed. Consider comparing that to a powerlifter. If their squat is 450 but they never truly hit anything over 400, it’s unlikely they’ll be able to maintain their strength in those higher ranges for weeks or months on end.

Dose sprints into training. Track live if possible and see if they get it in training. If not, get them building up into it. Some coaches worry about doing it at the end of training when fatigue has set in. Definitely something to take into consideration but in a match, they may have to do it in the 85th minute once they are incredibly fatigued. When I have any concerns with a player (high sprint count, high acute load of HSR, sore psoas, etc.) they’ll do their sprint on their own, building up gradually. If they feel good and we’ve built up our chronic load in-season, the group will race either in 2s or as a group. Max intent is important, and it never hurts to bring a little competition into training to bring out the best in athletes.

High-speed running density: 450m isn’t necessarily 450m

In a study using an Irish rugby team, researchers looked at what they call “high-speed running density” (Tierney, Malone, Delahunt, 2018). Simply put, it is the number of high-speed efforts divided by the total HSR volume multiplied by 100. This directly relates to the first point I made but is a way to track it using a singular number i.e. by having your system report the HSR density. It is a different way to track and represent the data, but it is another layer to consider going forward.

Two athletes may have the same volume of HSR exposure in a particular match. However, one athlete may have gotten their 450m over the course of 10 efforts whereas another one may have gotten it over the course of 35 efforts. Having a high percentage is going to mean that the athlete challenged their muscular and neurological systems again and again and again whereas the lower percentages mean that they had longer but sustained runs. How this affects your decision making is up to you, but I know that I am going to place an asterisk by those that have that higher percentage and constantly had to dig into their reserves to continue competing.

Hopefully, these concepts spur a bit of thought on your own process. Interested to hear your thoughts and ideas as it pertains to maximal effort running. It is surely a topic I will continue to address going forward.

References

Chumanov, E.S., Heiderscheit, B.C., Thelen, D.G. (2007). The effect of speed and influence of individual muscles on hamstring mechanics during the swing phase of sprinting. Journal of Biomechanics, 40, 3555-3562.

YLM Sports (2020). Figure 1. Ylmsportsscience.com. Return to play & Injury prevention: running fast is much different than sprinting!

Tierney, P., Malone, S., & Delahunt, E. (2018). High-speed running density: a new concept.Science Performance and Science Reports, v1, 1-4.